There are a variety of options available for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

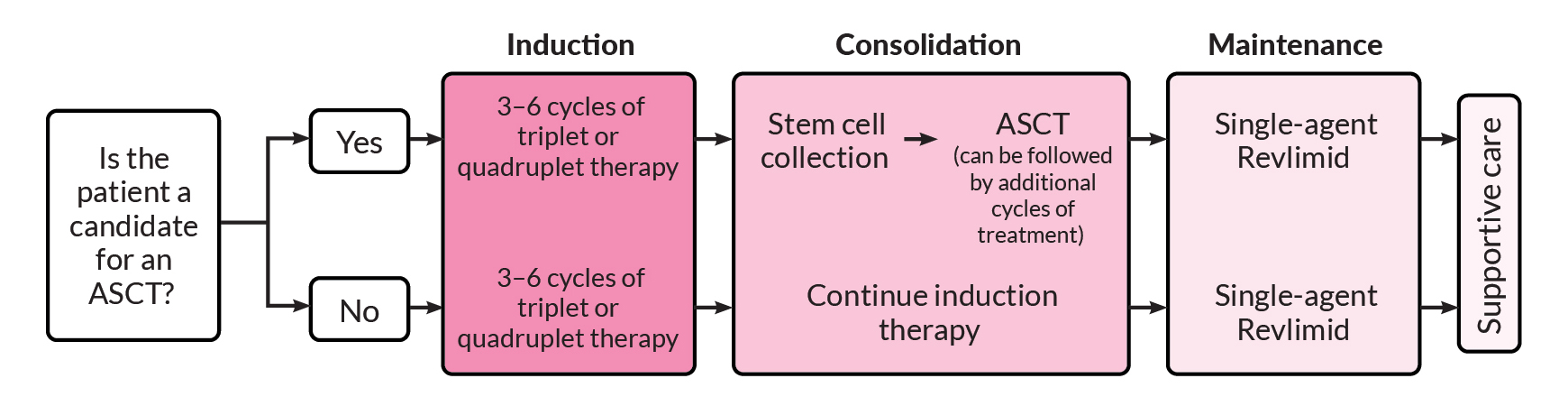

Induction therapy, or front-line therapy, typically consists of a three-drug or four-drug combination regimen given over three to four cycles, each of which typically lasts 3 or 4 weeks.

Three-drug regimens (triplet therapy) generally include an immunomodulatory drug (Revlimid or Pomalyst), a proteasome inhibitor (Velcade, Kyprolis, or Ninlaro), and a steroid (dexamethasone or, less commonly, prednisone).

Four-drug regimens (quadruplet therapy) are similar to three-drug regimens but also include an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody (Darzalex or Sarclisa).

The choice of initial treatment depends on many factors. These include the features of your myeloma, the risk of side effects, convenience for you, and the familiarity of the doctor with the available treatment options.

One of the first questions that must be answered, by both you and your doctor, is whether you are a candidate for high-dose chemotherapy followed by an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Determining whether transplant is an option is an important factor in selecting induction therapy. If you are a candidate for transplant, you may choose to have a transplant after three or four cycles of induction therapy or you may decide to complete induction therapy and consider transplant later.

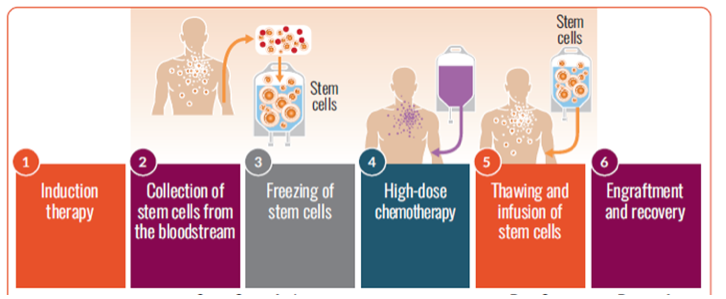

If you are eligible and decide to proceed with a transplant, you will usually receive induction therapy followed by stem cell collection and storage, high-dose melphalan chemotherapy, and ASCT. This is then followed by consolidation and/or maintenance therapy. If you opt to delay ASCT, your stem cells would still be collected and stored for use in the future.

If you are not eligible for a transplant, you will go directly from induction therapy to consolidation or maintenance therapy, depending on your response to induction therapy.

Your care team can help decide which course of therapy is best for you, based on the characteristics of your myeloma, your treatment goals, and your personal situation.

Bone marrow transplants are no longer done in multiple myeloma. Instead, almost all transplants in multiple myeloma use cells obtained from the blood; these are referred to as peripheral blood stem cell transplants.

The main type of stem cell transplant performed for multiple myeloma patients is ASCT, which uses your own stem cells. Another type of transplant, allogeneic stem cell transplant, uses stem cells from a donor and is rarely used outside of clinical studies.

ASCT, in combination with high-dose chemotherapy (usually melphalan), is a treatment that, for many eligible myeloma patients, offers a very good chance for a long-lasting response. High-dose chemotherapy, though effective in killing myeloma cells, also destroys normal blood-forming cells (hematopoietic stem cells) in the bone marrow. Stem cell transplantation replaces these important cells.

Autologous stem cell transplantation steps

If you are eligible for a transplant, you are encouraged to have stem cells collected (harvested) so the cells are available if you choose to undergo transplantation at some point in the future.

The cells are stored until they are needed for the transplant. The stored stem cells are infused back into your blood. This procedure may be inpatient or outpatient, depending on the center and/or your preference.

After induction and autologous stem cell transplant, you will undergo maintenance (continuous) therapy. Maintenance therapy is given after induction therapy to help keep the myeloma from growing back. Maintenance therapy improves survival and can increase the length of time you spend in remission, but it is also associated with treatment side effects.

Revlimid is an FDA-approved maintenance therapy option; Velcade and Ninlaro are also acceptable options, particularly if you cannot tolerate Revlimid. There are also several clinical studies looking at the effectiveness of different regimens for maintenance therapy, including Kyprolis, Darzalex, and Empliciti, alone and in combination with other treatments.

Treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma

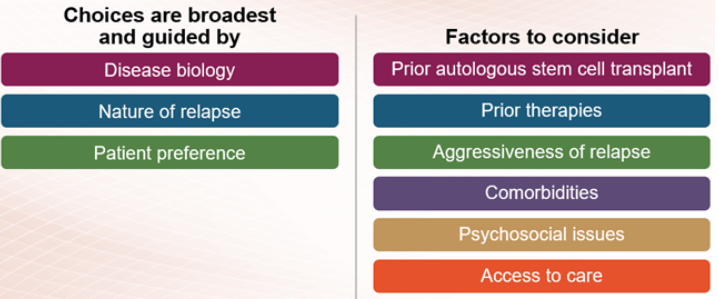

If your multiple myeloma is resistant to therapy (refractory) or if your myeloma returns after an initial response to treatment (relapsed), you are said to have relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.

There are many effective treatment options for relapsed myeloma—more are being tested in clinical studies—so if your myeloma relapses, you should not lose hope or think that there are no chances for an effective treatment.

Therapies for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma are selected based on the number of prior myeloma treatments you have received and which treatments you already received (and may no longer work). Some treatments are used for patients who have had three or fewer treatments (who are said to be in early relapse), and different treatments tend to be used for patients who have received more than three prior therapies.

Therapies for early relapse

If you have early relapsed multiple myeloma, the treatment options include immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies. This may include repeating the treatment used in your induction therapy or trying different therapies from the same class of treatment as those used for induction. In addition, drugs that work in new ways (novel mechanisms), like Xpovio (selinexor), may be used to treat early relapsed multiple myeloma. Combinations of these agents with dexamethasone are used to treat early relapse.

If your myeloma does not respond to immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies, you are said to be triple-class refractory. Treatment options for triple-class refractory multiple myeloma have seen great advances in the last few years. In addition to novel treatments like Xpovio, therapies used to treat triple-class refractory myeloma include bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell therapy.

Currently available treatments for patients with triple-class refractory disease:

Xpovio

Abecma

Carvykti

Tecvayli

Talvey

Elrexfio

If you have relapsed or refractory myeloma, there are new agents and therapies under investigation that may provide benefit. Your care team can help you find an appropriate study. You can also speak with an MMRF Patient Navigator for more information.

Myeloma treatment can also involve what are referred to as supportive care therapies, which help in the management of myeloma symptoms and treatment side effects.

Proteasome inhibitors are an important class of multiple myeloma treatments and are used at all stages of disease.

Three proteasome inhibitors are approved for use in multiple myeloma treatment: Velcade (bortezomib), Kyprolis (carfilzomib), and Ninlaro (ixazomib).

Immunomodulatory drugs are an important class of standard treatments used to treat multiple myeloma. They work by activating certain cells in the immune system, preventing myeloma cell growth, and even by directly killing myeloma cells.

The immunomodulatory drugs currently used to treat multiple myeloma include the oral agents Revlimid (lenalidomide), Pomalyst (pomalidomide), and, less commonly, Thalomid (thalidomide).

Revlimid, given in combination with dexamethasone, is used to treat all stages of multiple myeloma.

Monoclonal antibodies are agents that fight disease by activating your immune system. These drugs enhance the cancer-fighting abilities of your own immune system by targeting multiple myeloma cells.

Currently, the most commonly used antibodies are Empliciti (elotuzumab), Darzalex (daratumumab), and Sarclisa (isatuximab).

Bispecific antibodies are another type of antibody-based immunotherapy. There are currently three bispecific antibody therapies FDA-approved for myeloma patients who have received at least four prior lines of therapy: Tecvayli (teclistamab), Talvey (talquetamab), and Elrexfio (elranatamab).

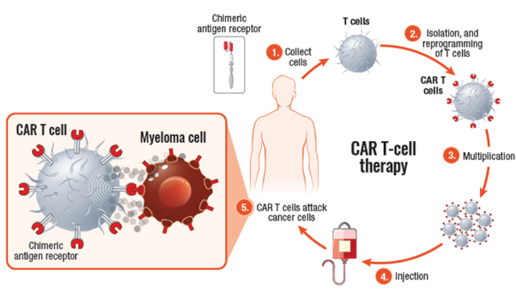

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy uses your own white blood cells to fight myeloma. In CAR T-cell therapy, your T cells are collected from your blood, modified in a lab to be more effective in identifying and attacking myeloma cells, and then infused back into your body—as “supercharged” myeloma fighters. These “supercharged” T cells are able to find and kill myeloma cells.

CAR T cells

CAR T-cell agents currently approved for use in patients with multiple myeloma include Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel) and Carvykti (ciltacabtagene autoleucel). Both are BCMA-directed, meaning that the patient’s T cells are collected, altered so that they can recognize BCMA on the surface of myeloma cells, and infused back into the patient, where they kill the myeloma cells.

Some of the newest drugs used to treat multiple myeloma do not fit the classification of any existing drugs. These new drugs work in different ways than drugs in the other classes—that is, they have novel mechanisms of action.

Xpovio (selinexor) is the first drug from a category that is referred to as selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINE). Xpovio is an oral drug typically used in combination with dexamethasone or Velcade and dexamethasone. It is given to patients who have previously received at least four prior treatment regimens and are refractory to proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, and Darzalex.

Chemotherapy uses drugs that kill cells that are in the process of dividing. Because cancer cells grow and divide more frequently than most healthy cells, they are affected more than normal cells. However, some healthy cells will be affected by chemotherapy, as well. This is what causes side effects. Most side effects can be prevented or reduced.

In the treatment of multiple myeloma, chemotherapy is most often used in preparation for an autologous stem cell transplant, but can also be used if you have relapsed or become refractory to prior treatments and may include these treatments:

Some chemotherapy drugs are given orally, and some are given intravenously. Often, several drugs are given together, because combining them has been shown to work better at stopping tumors while causing fewer side effects.

Chemotherapy treatments are given in schedules called cycles, which typically last 3 or 4 weeks. Some drugs are taken daily, and others are given weekly or once per cycle. One course of treatment typically consists of four to six cycles, lasting a total of 4 to 6 months.

Steroids are another important class of multiple myeloma treatment and are used at all stages of the disease. In high doses, steroids can kill multiple myeloma cells. They can also decrease inflammation, helping relieve pain and pressure. Additionally, steroids may be used to reduce nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy and other forms of treatment.

Two steroids that are commonly used in multiple myeloma are dexamethasone and prednisone. They may be used in combination with other multiple myeloma drugs.

Side effects of steroids include high blood sugar, weight gain, sleeping problems, and changes in mood. Over time, steroids may suppress the immune system and weaken bones. These side effects usually go away after patients stop taking these drugs.

Many medications for multiple myeloma can cause constipation, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Though some people find it embarrassing to discuss these problems, your doctors and nurses are used to discussing them and can often easily treat them.

Constipation

Your doctor may prescribe a stool softener or laxative to help relieve constipation. Additionally, a diet high in fiber with plenty of fruits, vegetables, lentils, whole grains, and bran-based cereals can help. Drinking plenty of water is important, and hot drinks like coffee or tea can help stimulate a bowel movement. Gentle exercise, such as walking or swimming, can also be helpful.

Diarrhea

If you experience severe diarrhea (more than six loose stools per day for two days), let your doctor know right away. He or she will recommend an antidiarrheal medicine (either over-the-counter or prescription) and may advise you to take a fiber supplement. It’s important to stay hydrated when experiencing diarrhea, so drink plenty of water and avoid coffee and alcohol. Eating small, light meals slowly throughout the day can be helpful.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea is commonly experienced by people with multiple myeloma, due to the disease itself or to certain treatments. Drugs called antiemetics are used to treat nausea and vomiting. Depending on the multiple myeloma treatment you’re receiving, your doctor may even prescribe an antiemetic drug to stop nausea and vomiting before it starts. Drinking lots of fluids and eating small meals throughout the day can also help manage nausea and vomiting.

Decreases in blood cell count can be caused by multiple myeloma itself and also by many myeloma therapies. Proteasome inhibitors such as Velcade and Kyprolis, immunomodulatory drugs such as Revlimid and Pomalyst, and antibodies such as Empliciti can decrease the numbers of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

Blood cell counts are carefully monitored by your doctor. If they become too low, myeloma therapy may be delayed or dose adjustments may be made until the blood cells increase to normal levels.

Maintaining good nutrition is important in helping blood counts stay in the normal range. Your doctor may also prescribe growth factors such as erythropoietin to stimulate red blood cell production and/or colony-stimulating factors such as G-CSF or GM-CSF to stimulate white blood cell production.

Though multiple myeloma patients are at higher risk of infection because of the disease itself, many myeloma treatments also increase the risk of infection because of their effects on blood counts—specifically white blood cells, which help fight infection.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is a common and serious side effect of bispecific antibody and CAR T-cell therapies. CRS can occur after infusion of the therapy. It causes fevers, chills, and low blood pressure. For this reason, your healthcare team will closely monitor you after treatment for signs of CRS. Treatment for CRS may vary but will generally include medication to reduce inflammation, as well as other treatments depending on your symptoms.

Neurotoxicity is another serious complication that may result from bispecific antibodies or CAR T-cell therapy. Most patients experience mild symptoms like confusion but, in some cases, patients experience severe symptoms like delirium or seizures. Your healthcare team will take steps to minimize the likelihood of neurotoxicity, monitor for symptoms, and promptly treat it.

Explore complementary care, adjunctive treatments, and, when needed, hospice options. Be sure to speak with your healthcare team if you feel you would benefit from any of these supportive care approaches. Some medical centers may offer such services for free or at a reduced cost for cancer patients.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy, which uses high-energy particles or rays to damage cancer cells and prevent them from growing, has proven effective in treating complications from bone disease caused by myeloma. In low doses, local radiation therapy (radiation delivered to a specific part of the body) can help relieve uncontrolled pain or prevent or treat bone fractures or spinal-cord compression. In high doses, local radiation therapy (sometimes given with chemotherapy) is used to treat solitary tumors in bone or soft tissue (plasmacytomas). Radiation therapy may also be called radiotherapy, x-ray therapy, or irradiation.

Adjunctive treatments

In addition to receiving medical treatments directed at managing your disease, you will most likely require additional treatments to help manage symptoms and treatment side effects.

Drug therapies can help relieve multiple myeloma symptoms, such as bone disease or kidney failure and side effects from treatments such as blood clots.