There are many paths forward from a multiple myeloma diagnosis: understanding the disease is an important first step to managing it.

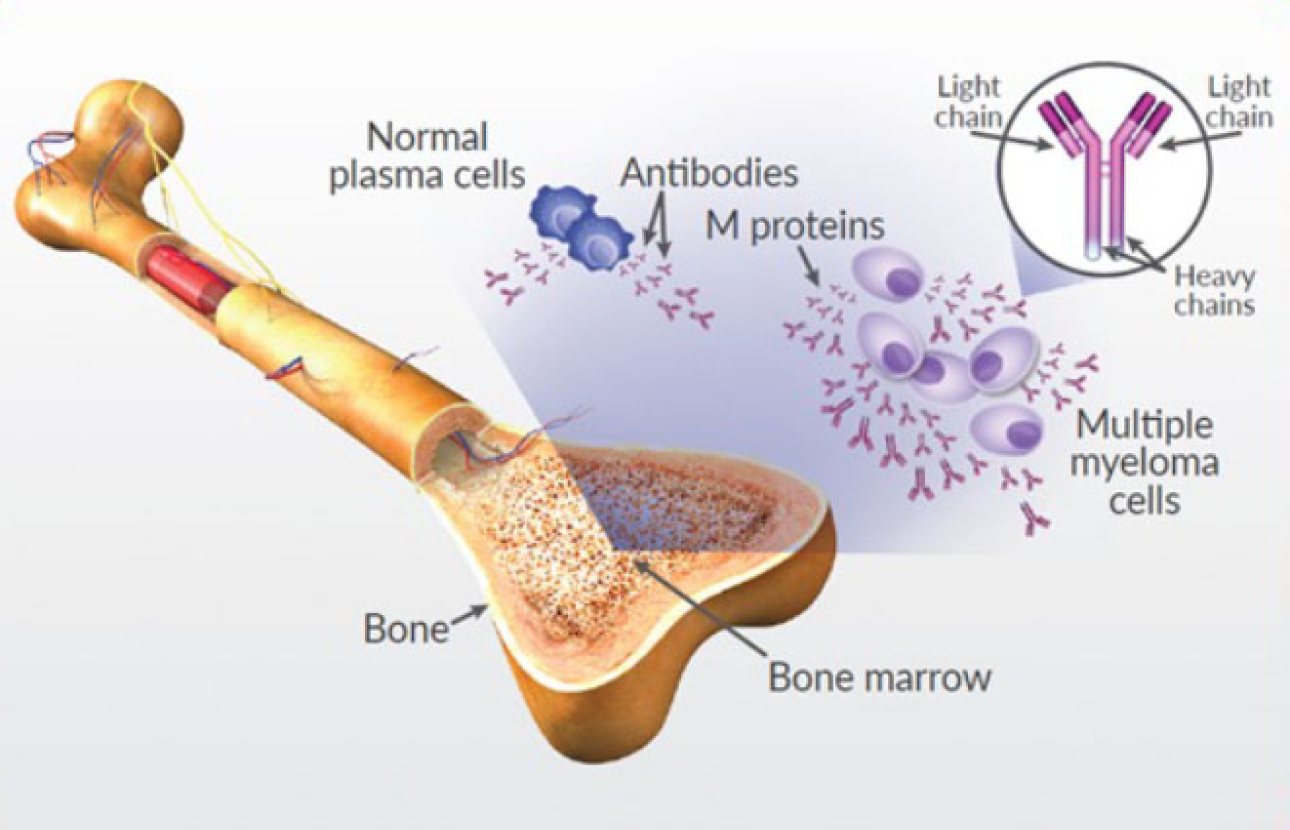

Multiple myeloma is a blood cancer that develops in plasma cells in the bone marrow—the soft, spongy tissue at the center of your bones. In healthy bone marrow, normal plasma cells make antibodies to protect your body from infection.

In multiple myeloma, plasma cells are transformed into cancerous cells that grow out of control, crowding out the normal cells that help fight infection. These malignant plasma cells then produce an abnormal antibody called M protein, high levels of which are a hallmark characteristic of multiple myeloma.

In recent years, researchers have developed a better understanding of how multiple myeloma develops, but the exact cause has not yet been identified. Like all cancers, multiple myeloma is heterogeneous (that is, it takes many forms), meaning that each case is unique.

Multiple myeloma is caused by certain genetic mutations, and these mutations are different from person to person. But though certain mutations have been identified as risk factors for myeloma, multiple myeloma is not thought to be a hereditary disease. That is to say, the mutations that cause multiple myeloma are not passed down through families the way certain physical traits or diseases like cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease are. Rather, the mutations that cause myeloma likely develop spontaneously as people age.

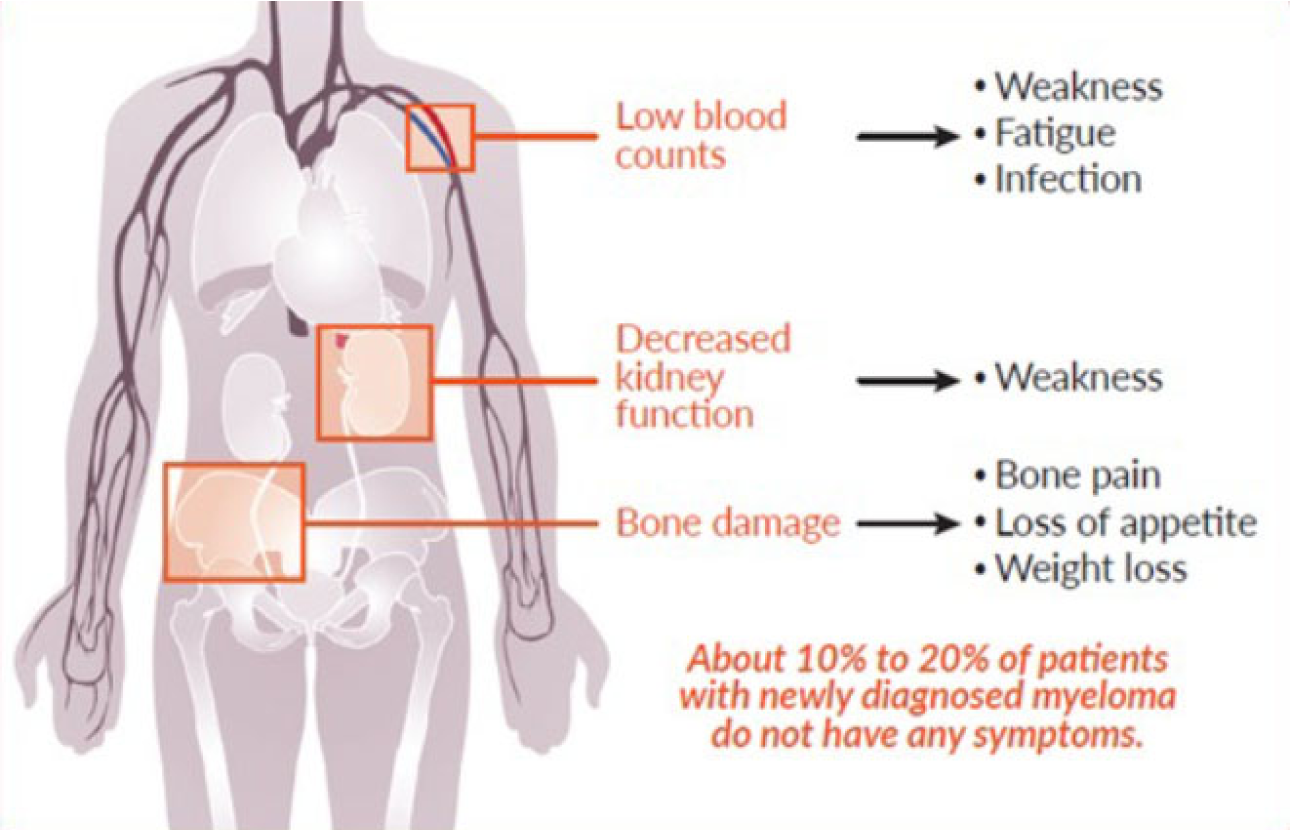

As myeloma cells multiply in the bone marrow, they crowd out normal cells, meaning that there is less room for—and decreased numbers of—red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Reduction of blood cells can cause anemia, excessive bleeding, and decreased ability to fight infection. The buildup of M protein in the blood and urine can damage the kidneys and other organs.

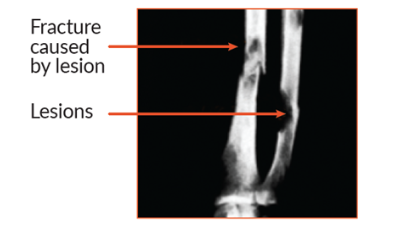

Myeloma cells may activate other cells in the marrow that can damage your bones, which can cause bone pain and weakened spots on bones (called osteolytic lesions). This bone destruction increases the risk of fractures and can also lead to increased levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia).

Multiple myeloma symptoms vary from person to person. Often, in the early stages of disease, there are no obvious symptoms. When they are present, symptoms may be vague or similar to those of other conditions.

If your doctor suspects that you may have multiple myeloma, they may run several different urine and blood tests to confirm the diagnosis.

Decreased production of red blood cells can result in a complication called anemia. Some multiple myeloma treatments can contribute to anemia, as well.

Anemia is typically defined as an abnormally low hemoglobin (Hb) level. Hemoglobin, a substance found in red blood cells, carries oxygen from the lungs to the tissues in the body.

Anemia can cause weakness, fatigue, shortness of breath, and dizziness. Over 60% of multiple myeloma patients have anemia at the time they are diagnosed. Most patients who do not have anemia at the time of myeloma diagnosis become anemic at some point of their disease.

Several therapies are available to treat anemia, including supplementation with iron, folate, or vitamin B12 and treatment with medications called red blood cell growth factors. For people with severe anemia, blood transfusions may be needed.

The low white blood cell count caused by multiple myeloma also damages the immune system, as white blood cells are important in fighting off infection. Frequent infections can also contribute to fatigue.

Although multiple myeloma leads to an increased level of antibodies, the antibodies produced by multiple myeloma cells are ineffective, and the multiple myeloma cells crowd out the healthy cells that produce functional, disease-fighting antibodies.

By impairing the immune system in this way, multiple myeloma reduces the body’s ability to prevent or fight off infections. As a result, people with multiple myeloma are more susceptible to infections. In fact, they are about 15 times more likely to get an infection than people without multiple myeloma.

However, there are steps you can take to reduce your risk of infection:

To further reduce your risk of infection, your doctor may use medications such as intravenous antibody therapy (immunoglobulin IgG), antifungal medications, colony-stimulating factors, and preventive shingles treatments or antibiotics.

Tell your doctor right away if you have any symptoms of infection, such as a fever over 100.5°, chills or sweating, muscle aches, coughing, sore throat, pain/redness at the site of an open cut, fatigue, or diarrhea.

Decreased platelet production can result in impaired blood clotting. Bleeding from a cut may continue for a longer time than normal. Also, patients may experience increased bruising under the skin from mild injuries sustained in the course of normal activities. To reduce the risk of uncontrolled bleeding, patients should limit alcohol consumption and stop taking over-the-counter medications such as aspirin and ibuprofen. Severe thrombocytopenia may require a platelet transfusion, where the patient receives platelets collected from a donor.

In people with multiple myeloma, excess M protein and calcium in the blood overwork the kidneys as they filter blood. As a result, the kidneys may fail to function normally. If the impaired kidney function is so severe that the kidneys are unable to do their job (filtering waste from the blood), it results in kidney failure.

More than half of people with multiple myeloma experience a decrease in their kidney (renal) function at some point in the course of their disease.

Most patients with kidney disease do not have any symptoms. Usually, it isn’t until the kidneys are severely compromised that a patient knows they have kidney problems. A reduction in the amount of urine is one sign of kidney problems, so it is important to let your doctor know if you experience any changes in urination.

If your doctor suspects impaired kidney function, they will likely perform blood tests to detect certain proteins (such as creatinine) that may indicate impaired kidney function.

Staying well hydrated is one way to manage impaired kidney function. Your doctor may also advise you to avoid alcohol and anti-inflammatory drugs (such as Advil, Motrin, or Aleve). You should also make sure that your blood pressure is well controlled.

Depending on the severity of your kidney impairment, you may need to undergo plasmapheresis (a procedure where some of your blood is removed, processed, and returned) or dialysis (a procedure where waste products are removed from your blood through use of a special machine).

Multiple myeloma leads to bone loss in two ways. First, multiple myeloma cells form masses in the bone marrow that disrupt the normal structure of the surrounding bone. Second, myeloma cells boost the activity of other cells that are responsible for breaking down bone. The action of these cells causes small holes (called lytic lesions) to develop in bones, which weakens them. Physicians are able to view these holes when they take an x-ray.

Bone disease in multiple myeloma

About 85% of people with multiple myeloma have some type of bone damage (osteolytic lesions) or loss (osteoporosis). The most commonly affected areas are the spine, pelvis, and rib cage.

With weakened bones, people with multiple myeloma often experience bone pain and have an increased risk of fracture or vertebral bone collapse, which may cause spinal cord compression, a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment to avoid long-term damage.

Common ways to manage bone damage in people with multiple myeloma include exercise, supplementation with calcium and vitamin D, use of bisphosphonates and other medications, orthopedic interventions, low-dose radiation therapy.

Bone destruction can increase the level of calcium in the blood—a condition called hypercalcemia—which can be a serious problem if not treated immediately. Severe hypercalcemia can result in coma or cardiac arrest, so it’s important to identify and treat it quickly.

Let your doctor know right away if you experience any of the following symptoms:

Knowing what kind of myeloma you have is important in helping your doctor decide when it is appropriate to begin treatment. Having that knowledge plays an important role in determining the stage of multiple myeloma.

Risk of progression to multiple myeloma or related conditions: 1% per year

Risk of progression to active myeloma: 10% per year

MGUS is a condition that occurs when a small amount of M protein is detected in the blood, but no other criteria of multiple myeloma (such as a tumor or bone lesions) are present. MGUS occurs in about 1% of the general population and in about 3% of healthy individuals over 50. MGUS is two to three times more common in the Black community for reasons that are unknown. Also, people who have a first-degree relative (a parent, sibling, or child) with a blood cancer (not just myeloma) are at a higher risk of having MGUS.

MGUS does not usually cause problems or require treatment but, in rare cases (1%–2%), it can develop into multiple myeloma. People living with MGUS receive regular checkups to ensure that it does not progress.

Smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) is a precancerous condition that is diagnosed when low levels of M protein are found in the blood and a slightly increased number of plasma cells are found in the bone marrow. SMM is a stage between MGUS and multiple myeloma, and patients with SMM have a higher risk of progressing to myeloma than do patients with MGUS.

The commonly accepted approach to managing SMM is watchful waiting, which means the doctor monitors the condition but will only treat it if symptoms worsen.

Many studies have shown a benefit of treating SMM before symptoms change, particularly in patients who have any of the genetic mutations that are recognized as risk factors for full-blown multiple myeloma. Early intervention in these patients has been successful in preventing multiple myeloma development, but this should preferably occur in a clinical trial setting. Additional studies are ongoing and more evidence of the benefit of treating SMM is needed before this becomes a standard of care.

Precursor condition criteria

| MGUS | SMM | |

| M protein level | Under 3 g/dL in blood | At least 3 g/dL in blood or at least 500 mg/24 hrs in urine |

| Plasma cells in bone marrow | Under 10% | At least 10%–60% |

| Clinical features | No myeloma-defining events* | No myeloma-defining events* |

*CRAB, calcium elevation, renal insufficiency, anemia, bone disease.

Multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells, is part of a disease spectrum; it is the last stage of a process that generally begins with MGUS and progresses to SMM before advancing to myeloma. Active multiple myeloma is differentiated from the precursor conditions based on the presence of myeloma-defining events or one or more CRAB criteria.

![]()

| Multiple myeloma | |

| M protein level | At least 3 g/dL in blood or at least 500 mg/24 hrs in urine |

| Plasma cells in bone marrow | At least 60% |

| Clinical features | At least 1 myeloma-defining event* (CRAB feature or SLiM feature) |

Clinical Characteristics of Multiple Myeloma

An individual with multiple myeloma typically has several clinical features that affect their bones, blood, and kidneys. These features are often referred to by doctors as the CRAB criteria, which stands for high levels of calcium in their blood, kidney (renal) problems, low levels of red blood cells (anemia); and bone damage, such as weakening of the bones or fractures. The presence of CRAB criteria defines active multiple myeloma.

Individuals who are found to have slightly elevated M protein levels in their blood but do not have any symptoms and do not meet CRAB criteria may have one of two conditions that can lead to multiple myeloma—that is, a multiple myeloma precursor condition. Because most people are not screened for precursor conditions (doctors do not routinely order tests to measure M protein) and there are no signs or symptoms associated with precursor conditions, diagnosis usually only happens incidentally, such as when a doctor investigating another health issue happens to discover M protein in the blood or urine.

Non-secretory multiple myeloma (nsMM)

This is a rare (2% to 4%) form of myeloma where the cancerous plasma cells do not secrete M protein or light chains. The lack of these proteins in the blood makes this form of myeloma much harder to evaluate and monitor over time, and patients with this form of myeloma are often not eligible for clinical trials due to this issue. In addition, kidney issues are less prevalent in this form of myeloma, since protein in the blood is lower. In general, nsMM is treated similarly to and can have similar outcomes as secretory forms of the disease. Monitoring of nsMM may require more invasive types of assays (ie. more bone marrow aspirates).

SLiM, over 60% plasma cells in bone marrow, free light chain involved to uninvolved ratio over 100, more than 1 focal lesion on MRI.

A single group of myeloma cells is called a solitary plasmacytoma. When it grows outside of bone, it is called an extramedullary plasmacytoma; when it grows inside a bone, it is called a solitary plasmacytoma.

Solitary plasmacytomas can affect any bone but tend to occur most frequently in the bones along the spinal column. They are normally diagnosed by a biopsy that reveals abnormal plasma cells. With solitary plasmacytomas, bone imaging (x-rays, positron-emission tomography [PET] scan, or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) detects only a single lesion. Blood tests show no anemia or high calcium levels, and kidney function is normal.

Solitary plasmacytomas are rare. They are commonly treated with radiation therapy and rarely require surgery. Prognosis with radiation alone is usually excellent, but there is a risk that a solitary plasmacytoma could recur and progress to multiple myeloma. People with solitary plasmacytoma have long-term follow-up appointments to ensure that they remain in remission.

Research has greatly improved the prognosis—or predicted course of the disease—for multiple myeloma patients.

Symptoms, age, classification (subtype of myeloma), and stage of disease are some of the significant factors that contribute to your prognosis. Several clinical and laboratory findings (prognostic indicators) help determine how fast the myeloma is growing, the extent of disease, the biological makeup, the response to therapy, and the overall health status of the patient.

Myeloma staging is based on the results of diagnostic testing, and a stage is assigned to indicate the extent of disease. Determining the stage of your disease is one of the most significant factors in developing a personalized treatment plan.

The most commonly used staging system is the Revised-International Staging System (R-ISS), which is based on the results of FISH testing of the bone marrow and three blood tests: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), beta-2 microglobulin (β2M), and albumin.

Myeloma Staging

| R-ISS stage | Laboratory measurements |

|---|---|

| I |

|

| II | All other possible combinations |

| III |

|

*High-risk chromosomal abnormality: del(17p) and/or t(4;14) and/or t(14;16).

Just as every person is different, every multiple myeloma diagnosis is unique. Survival statistics can be informative, but they do not provide the entire picture.

When looking at statistics, it’s important to understand that statistics do not and cannot tell what will happen to you: they can tell only what has happened to others in the past. And the relevance of statistics is limited by the extent to which they are reporting about people who are similar to you in terms of patient demographics, myeloma subtype, and treatment options.

This refers to the number of individuals still living 5 years after being diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

(Source: National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database)